Architecture Begins With the User

Software exists to serve users, right? So why does every discussion about architecture start with infrastructure, frameworks, and data models instead of those users? We debate microservices architectures, argue about API design, and design systems with Kubernetes and Kafka that work beautifully at scale but never pause to consider who this complexity serves.

Meanwhile, the developers who work closest to the users often don’t participate in bigger architectural decisions, sometimes excluded, sometimes by their own choice.

I think it’s time to flip everything around. Let me show you what I mean, and why more front-end developers should be driving your top-level architecture.

Storytime

I recently found this line of code

<ItemView key={selectedItem.id} /> in our codebase. Take a minute and

guess what it does. I’ll tell you soon, but first, let me tell you a story.

A while back I was redesigning a page to make it more accessible to prepare for the

European Accessibility Act, and as part of this, I restructured some files. Everything

seemed to work fine but after a while I realized that only parts of the page were

actually updating when I changed the selected item. Production worked flawlessly. I

diffed the files but I couldn’t find anything related to data fetching in the changed

files. I reverted pretty much everything but nothing worked until I got back to this

code. As part of the restructure I had changed

<ItemView key={selectedItem.id} /> to

<ItemView />. It was the only child and since React only needs keys

when there are multiple children, I removed it.

Maybe it was obvious to you all along, but what

key={selectedItem.id} actually did was force React to completely recreate

the component when the item changed – essentially destroying and rebuilding that entire

piece of the interface, which triggered a fresh data fetch. I’m sure the developer who

wrote this thought it was a clever solution – a clever solution that caused hours of

debugging time.

This is architecture by accident.

This front-end example is just one of many. These shortcuts appear everywhere – in how services talk to each other, in how data flows through the system, in how teams coordinate. Architecture by accident isn’t a front-end problem or a back-end problem. It’s a systems problem.

These shortcuts pile up throughout the entire system. New features take longer and longer to build, and eventually we end up with a codebase that calls for a total rewrite.

The Root of the Problem

So why does this keep happening? I think the biggest problem is that architecture just isn’t part of the conversation anymore. Teams went “agile” and threw out thinking about the bigger picture entirely.

But you need that bigger picture. Without a clear direction, every small decision might actually be a step in the wrong direction. The problem is teams threw out all architectural thinking when they should have just thrown out the “architect designs everything then disappears” approach. Architects need to remain part of the team throughout the product’s entire lifecycle – adjusting course as reality changes.

But let’s be honest, teams don’t control this. It’s a leadership and organizational problem. Sometimes architects are never part of product teams at all. Sometimes they join but get pulled away the moment things get interesting. And sometimes they stick around but lack the authority to make changes within their team, or the organizational support to make the broader changes they see are needed.

So teams end up taking shortcuts. Not because they want to, but because they’re under pressure to show progress quickly. “We’ll fix it later” becomes the mantra. Except, later never comes. What looks like speed in the short term becomes the exact opposite over time – each new feature takes longer as the shortcuts pile up.

The goal of architecture is simple:

Minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system

– Robert C. Martin, Clean Architecture

When we don’t architect to meet that goal – especially the maintain part – the cost of each new feature grows with every release. Development velocity decreases over time. Teams spend more time fighting the system than building features. Eventually you get a system that cannot be updated, and as Robert C. Martin also points out: “It’s better to have a system that doesn’t work but can be updated than a system that works but cannot be updated.”

Users Don’t Care About Kubernetes

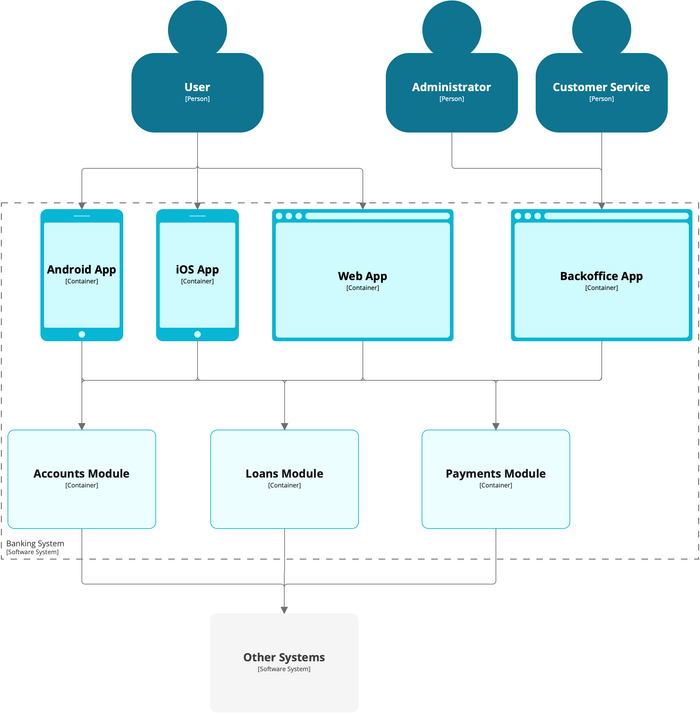

Let’s take a look at a typical user-facing system:

So here we have some apps, the architecture of the apps is probably MVVM, VIPER or something similar, the web app is React with Next.js, Redux Toolkit, TypeScript, Tailwind CSS, and Vite, using hooks, deployed with GitHub Actions to Vercel, monitored with Sentry, tested with Vitest and Playwright. They communicate with the server through an API gateway, or maybe GraphQL that connects to back-end services that use a hexagonal microservices architecture running in Docker containers in a Kubernetes cluster and they talk to each other using Kafka since we need to be event-driven.

This is how we normally describe our architecture.

The problem is that we are missing the user – users don’t care about Docker, MVVM, or Kafka, they don’t care that your database scales endlessly and is serverless, they don’t see your beautiful microservices architecture or your elegant API gateway, and they don’t experience your perfectly orchestrated Kubernetes deployments. What they care about is their account balance that won’t load. The search that can’t find what they’re looking for. The frustration when transferring money requires three different loading spinners that don’t coordinate. The pain of waiting years for new features.

“But what do you mean? We didn’t jump straight into buzzwords, first we made the back-end modular with separate modules for Accounts, Payments, and Loans.”

Yes, that’s great, but we stopped there. iOS developers build apps that consume the APIs. Web developers build separate applications. The backoffice team builds admin tools to manage the data. Maybe they’re all modularized internally – who knows. But here’s what matters: Users don’t care about any of this. They care about working features. So what happens when we want to add a simple feature?

You need the iOS team, the Android team, the web team, the API team, the backoffice team, and often teams that own the internal systems your back-end has become tightly coupled to – all coordinating their releases. I recently came across a small feature that involved nine different systems maintained by six different teams.

This is why users see loading spinners that don’t coordinate – each team built their piece independently. This is why new features take years.

So What’s the Alternative?

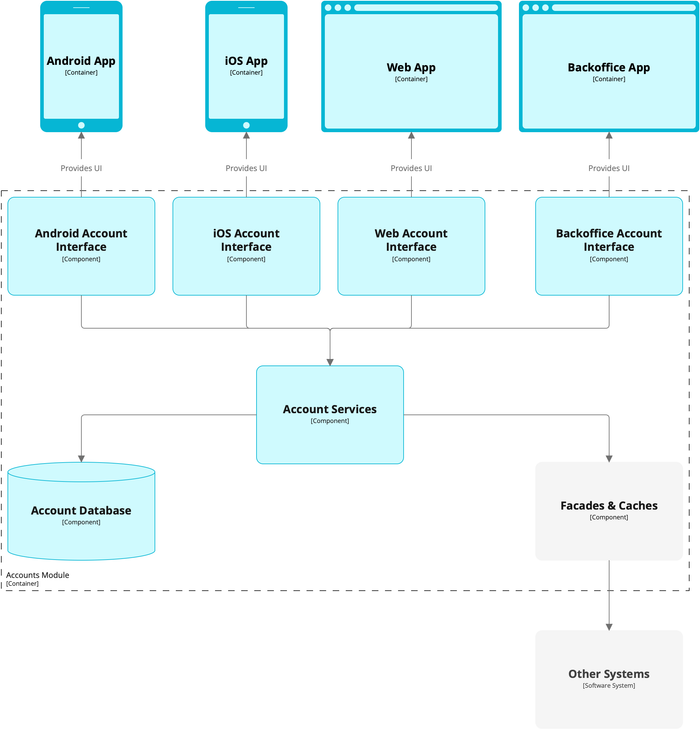

What if we flipped this around? What if everything for a feature – mobile interface, web interface, APIs, business logic, integrations, backoffice tools – was organized as one vertical slice, a feature module, and the apps were just coordination shells?

Here’s what the Accounts Module would actually contain:

This structure gives each feature module everything it needs to operate independently. The facades ensure you’re not tightly coupled to external systems. A team should be able to go to work one day and say:

Today, I’m going to create the world’s best savings account feature…

…and just do it. They don’t need to coordinate with the iOS team, wait for the API team, or depend on the backoffice team. They have everything they need to deliver that feature from start to finish. One team can work on multiple features, but each feature belongs to exactly one team.

So What’s the Catch?

I can hear the skepticism already. If feature modules are this great, why isn’t everyone building this way? Fair question. There are three real challenges you need to solve first, and they’re not easy to solve.

-

Slicing the domain correctly. Should user profiles be part of Accounts or separate? When a user disputes a loan payment, is that Accounts, Loans, or Payments? These are domain-driven design questions. They require deep understanding of user workflows and, critically, organizational support to restructure teams around these boundaries.

-

Solving this technically. You need to bring front-end interfaces into your feature modules. There are several approaches – micro frontends, Kotlin Multiplatform, well-structured packages, or Server-Driven UI which I’ve written extensively about, to name a few. Each has tradeoffs. The right choice depends on your team and context, but the important thing is to make this decision intentionally.

-

Bringing all these skills together. Each feature module needs iOS developers, Android developers, web developers, back-end developers within a single team. That’s a lot. Without a clear design system and strong architecture, this will be chaos. But honestly, with agentic coding increasingly handling implementation, I think it’s easier than ever to build teams that can handle this.

So yes, these are hard problems to solve. But here’s the thing – we need to think about these challenges upfront, before we jump into debates about frameworks and infrastructure. Start with the user. Start with the features they need. Then figure out how to organize your teams and architecture to deliver those features. The technical details come after.

Who Should Architect?

Currently, the answer is almost always back-end or “fullstack” developers. But they tend to focus on services, databases, and APIs. Performance and scalability. Important for sure, but often far from the user. Back-end systems absolutely need their own architecture – but when the top-level architectural decisions start with database schemas and API contracts instead of user needs, they’re not always the best fit.

What about front-end developers?

A feature isn’t just code. It’s a collaboration between business, design, and development. Front-end developers are caught between all of these, constantly adapting to forces beyond their control. They negotiate between:

- Designers who want the perfect user experience

- Back-end developers who think in terms of data and APIs

- Stakeholders who want business features delivered quickly

- The whims of browser vendors who change specifications on their own schedule

- Apple and Google who force platform requirement changes every single year

This constant negotiation between competing demands is exactly what system architects do. I’m not saying every front-end developer would be a great architect, but they’re better positioned for it than you might think.

But there’s a problem. In my experience, most front-end developers look down on architecture. Mention clean architecture or domain-driven design and other front-end developers look at you sideways. “Just use React and put everything in a hook. If that doesn’t work, add another framework that will solve all your problems.”

That needs to change. Front-end developers should be way more involved in architecture decisions at the highest level, and front-end architecture itself deserves far more attention. It’s a shame we’re not there yet. I plan to keep pushing this topic – in articles, in talks, wherever I can.

It’s time we stop creating architecture by accident and remember: Architecture Begins With the User.